What CEOs want you to know? - A synthesis

Today is the time to start learning everything about business. Whether you're a CTO, a Marketer, etc. to this post is a good place to start learning about that.

If you're already business leaders, it's the time to review basic business principles, then send this to your team members, your CTO, your Marketing Team, and so forth.

This post is hardly original - it's a synthesis of the book "What CEOs want you to know" and from a couple other reference resources that I will mention throughout the post.

Premise

I've been reporting directly to CEOs in my last two startups, and still I am now. I've been enjoying working with C-suite because it always feel like an adventure.

But there's something about CEOs that I quite don't understand:

- What do they actually think?

- What do they care about?

- How do they make decisions?

- How do they know that they're ... right?

Ram Charan, the author of the book "What CEOs want you to know", argue that everyone should spend a week to learn about business. This post is my attempt for that.

I highly recommended this book, it was an interesting and straight-to-the-point writing craft. if you find my synthesis interesting, buy and read the book from the author. If not, read it anyway.

In this post, I will go through 2 parts:

- (1) The four cores of the business with concrete examples of failed and successful businesses

- (2) Synthesize some key learnings and actionable steps to take

4 cores of the business

At the core, all businesses are the same. To big enterprises to small businesses, all shared the same business fundamentals

- (1) Market & Customers

- (2) Cash Generation

- (3) Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

- (4) Growth

I will go through this one by one, and give definition and examples.

(1) Customers

The goal of a business is to "generate" customers by serving products and services that are better than what competitors are doing.

But where do we find customers?

This is the job for the CEOs to find out. Best CEOs spend time staying close to the market and observe the customers to understand:

- What are customers buying?

- Why do they buy it?

- Are there any macro changes that affect their buying behaviors?

- Where's the market is heading?

These are a combination of understanding the unmet Jobs to be done of the customers, and anticipating future demands based on government policies, or on an on-going trends.

The mental models of CEO about is not so far apart from a street vendor who sells lemon juice.

A street vendor would:

- Observe their customers of why they buy juice and at what time

- Anticipate demand for future juice, like "should we focus on inventory orange or apple juice?"

- There's a trend of healthy eating lifestyle, perhaps people would want juice by diet sugar?

Most people think that CEOs must do data analysis rigorously to make a decision. But best CEOs don't just rely on just clinical data, they also use intuitions and common sense to make decisions on product and services.

That’s why CEOs like Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo, A. G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble, and Tim Cook of Apple make a point of visiting stores to make their own personal observations.”

Airbnb case

From early days Airbnb understood that travelers were seeking alternatives to traditional hotels, preferring local, home-like stays. Meanwhile, hosts wanted to make extra income by renting out unused spaces.

Travelers prefer the authentic local experience, often at lower prices than hotels, while hosts benefit from monetizing their underutilized assets (spare rooms or entire properties).

Airbnb recognized macro trends early on, such as the increasing preference for the “sharing economy” and “remote work,” which influenced its expansion into offering Airbnb Experiences (personalized travel activities) and remote work-friendly long-term stays.

Similar to the lemon juice vendor analogy, Airbnb’s CEO and leadership continuously observe these customer trends and tweak the product offerings, focusing on understanding what drives both guests and hosts to use the platform.

Steve Jobs case: "building without users"

Some people might say that CEOs must be visionary and dreamy with the implication that CEOs should overwrite the market's current need and build something of tomorrow - someone like Steve Jobs, who presumably known to have built iPhone "in a comma" without listening to customers.

This is sometimes served as an excuse for building superficial and cool-looking products without thinking about customers.

But nobody knew that Apple has conducted extensive usability testing, and observing users interact with the early prototypes. They paid close attention to users' body language - like squinting eyes or hunched shoulders - to detect frustration or confusion that users might not explicitly mention. This is not something that built "in a comma", known as talking-to-nobody type of building products.

It would be more assured if you looked statistically at cases of failed startups, a majority of the reasons was that they were building something that nobody wants.

(2) Cash generation

A good company must has the ability to maintain positive net cashflow.

Generate the cash of TODAY

Cashflow, as simply defined, is the disparity of money that flows in the company and those that go out:

Good cashflow reflects the company ability to generate cash and sustain itself effectively.

It's not the cash of the promised tomorrow, not the next week, not another next year. It's the cash that a company has today, to maintain its operation and immediate need.

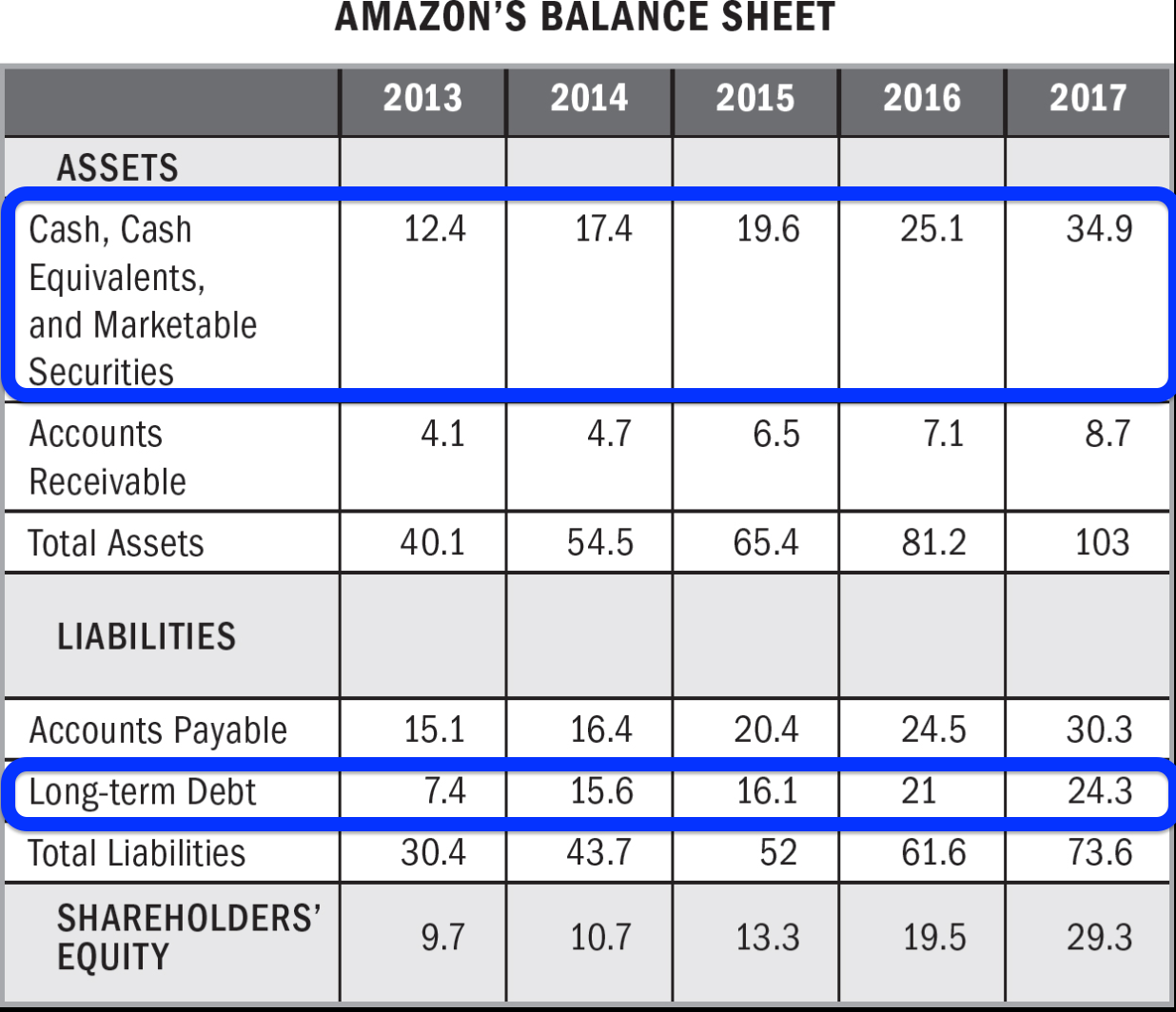

Now let's look at the example of Amazon's Balance Sheet. You might see that throughout 4 years from 2013 - 2017. Let's just look these line:

Looking at Amazon’s balance sheet from 2013 to 2017, we can observe a significant increase in cash and cash equivalents (from $12.4 billion in 2013 to $34.9 billion in 2017). This growth indicates Amazon’s strong cash generation capabilities, which allowed the company to expand its operations, make strategic investments, and maintain its liquidity.

The accounts payable also grew, but this shows Amazon’s effective management of supplier payments and other short-term liabilities. Balancing liabilities with growing cash reserves reflects a business with the ability to sustain itself in the short term, fund its growth, and weather any financial storms.

At first glance, Amazon’s long-term debt may seem significant. From 2013 to 2017, it grew from $7.4 billion to $24.3 billion. For someone unfamiliar with business financials, this number may seem alarming, as rising debt often gets a bad reputation.

However, it’s important to note that not all debt is a red flag, especially when it’s long-term debt. Long-term debt allows companies like Amazon to borrow money to invest in strategic growth, innovation, and expansion without needing immediate repayment.

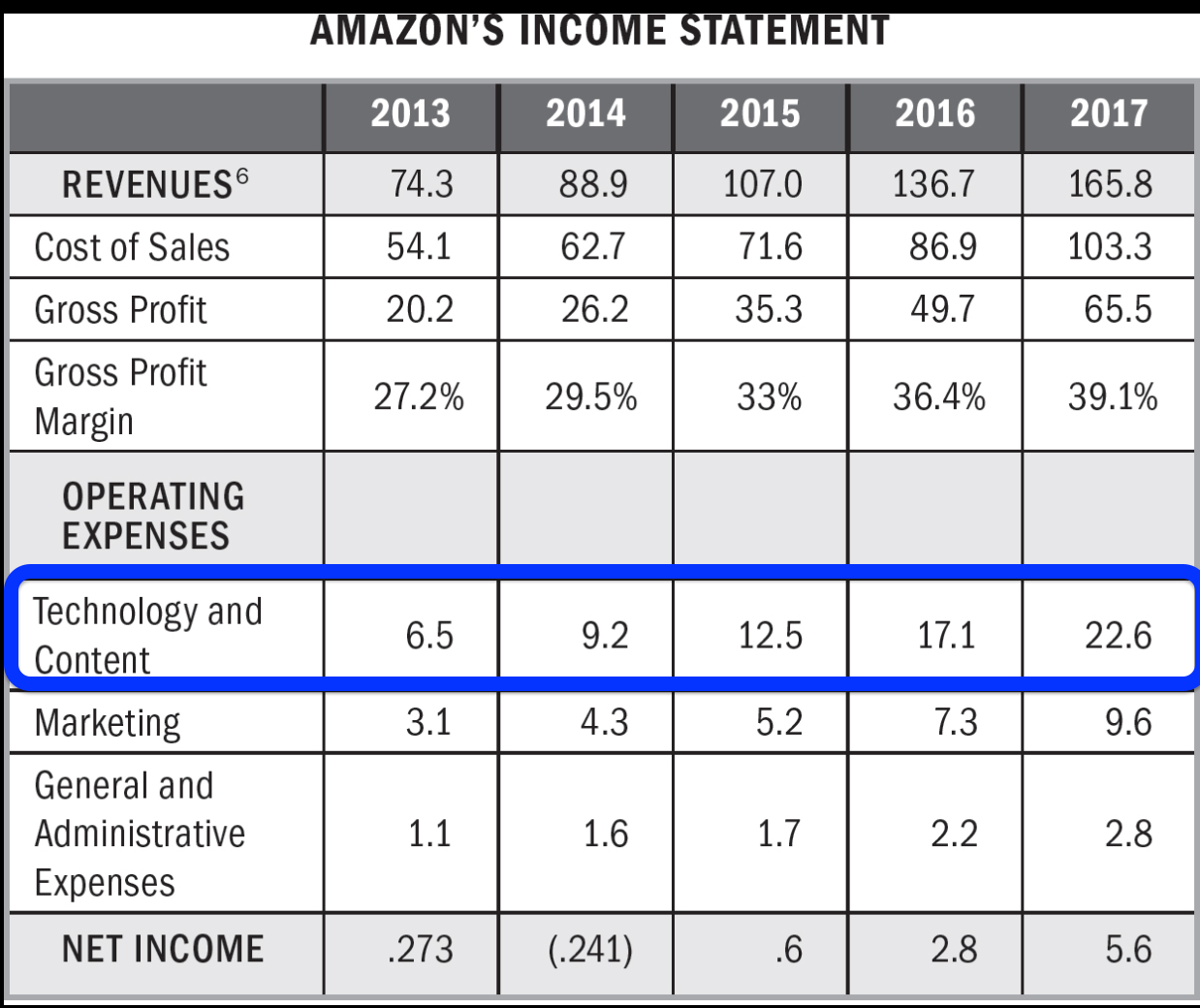

These good cashflow provides Amazon a leeway to invest the money into technology, which could then enhance the moneymaking capability of Amazon itself.

Cashflow > profit

Cashflow is even more important than profits, if you've been insisting on profits for a long time. If a business doesn’t have enough cash on hand to cover its immediate obligations, it could face operational problems, regardless of how profitable it looks on paper.

Sad cases happened to the automobile industry in 1980s. The automobile was infamously known for running out of cash. Volkswagen case in the early 1980s suffers cash shortage that brings the company to the verge of bankruptcy.